Address

304 North Cardinal St.

Dorchester Center, MA 02124

Work Hours

Monday to Friday: 7AM - 7PM

Weekend: 10AM - 5PM

As the online casino industry continues to grow in Canada, it’s essential to understand the legal and regulatory landscape, as well as the different types of online casinos available to Canadian players. This section provides an in-depth look at these crucial aspects.

At Bridgeliner, we understand that Canadian players have access to a wide range of online casinos, including download-based, web-based, and mobile casinos. Download-based casinos require players to install software on their computers, while web-based casinos can be accessed directly through a web browser without any downloads. Mobile casinos, on the other hand, are optimized for smartphones and tablets, allowing players to enjoy their favorite casino games on-the-go.

One of the primary draws of online casinos for Canadian players is the diverse range of games available. From classic table games to modern video slots, there’s something for every player’s preference. This section explores some of the most popular online casino games enjoyed by Canadians.

With the proliferation of online casinos catering to Canadian players, it’s crucial to prioritize security, fairness, and reliability when choosing a platform. This section provides valuable insights into the factors to consider when selecting a reputable online casino in Canada.

When selecting an online casino in Canada, it is crucial to prioritize licensing and regulation. Reputable online casinos are licensed and regulated by respected authorities, such as the Kahnawake Gaming Commission, the Malta Gaming Authority, or the United Kingdom Gambling Commission. These licensing bodies ensure that online casinos operate fairly, securely, and in compliance with industry standards.

Players can verify an online casino’s licensing and regulation by checking for the appropriate seals or logos on the casino’s website, as well as by researching the regulatory body’s website for a list of licensed operators.

Security and fair play are paramount considerations when choosing an online casino in Canada. Reputable online casinos employ state-of-the-art encryption technologies to safeguard players’ personal and financial information. Additionally, they utilize certified Random Number Generators (RNGs) to ensure that game outcomes are truly random and fair.

Independent auditing organizations, such as eCOGRA (eCommerce Online Gaming Regulation and Assurance), regularly test and certify online casinos for fair play and game integrity, providing an additional layer of confidence for Canadian players.

A reliable online casino in Canada should offer a wide range of banking and payment options to cater to diverse player preferences. Popular methods include credit and debit cards (Visa, Mastercard), e-wallets (Skrill, Neteller), bank transfers, and even cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin. Players should prioritize online casinos that offer secure and convenient payment methods, as well as prompt and hassle-free payouts.

One of the most appealing aspects of online casinos is the wide array of bonuses and promotions offered to both new and existing players. These incentives can significantly enhance the overall gaming experience and provide added value. This section explores the different types of bonuses and promotions available at online casinos in Canada.

While online casinos offer exciting gaming opportunities, it’s essential to practice responsible gambling to ensure a safe and enjoyable experience. This section highlights the importance of responsible gambling and outlines the tools and resources available to Canadian players.

While online casinos in Canada offer an exciting and convenient gaming experience, it is crucial for players to practice responsible gambling. Many reputable online casinos provide tools and resources to help players set deposit, loss, and time limits, ensuring they gamble within their means and maintain control over their playing habits.

For players who may be struggling with problem gambling, online casinos in Canada offer self-exclusion options and cooling-off periods. Self-exclusion allows players to voluntarily ban themselves from accessing an online casino for a specified period, while cooling-off periods provide a temporary break from gambling activities. These measures aim to promote responsible gambling and prevent potential harm.

In addition to the responsible gambling measures offered by online casinos, various support resources are available in Canada for individuals struggling with problem gambling. Organizations like the Canadian Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) and the Problem Gambling Institute of Ontario (PGIO) provide helplines, counseling services, and educational resources to support individuals and their families affected by problem gambling.

The future of online casinos in Canada is promising, with technological advancements and regulatory changes shaping the industry’s landscape. The adoption of virtual reality (VR) and augmented reality (AR) technologies could revolutionize the online casino experience, offering players an immersive and realistic gaming environment.

For years, Bridgeliner has been your go-to source for everything about Portland – its vibrant communities, rich cultural events, stunning architecture, and more. Today, we’re thrilled to announce that we’re expanding our coverage to bring you in-depth insights into the world of online casinos in Canada.

Our team is dedicated to providing comprehensive and trustworthy information to help you navigate the ever-growing online casino landscape in Canada. Whether you’re a seasoned player or new to the world of virtual gaming, we’ve got you covered.

In addition to our signature Portland content, you can now look forward to:

At Bridgeliner, we’re committed to delivering high-quality content that informs, entertains, and empowers our readers. Stay tuned as we embark on this exciting new chapter, bringing you the best of Portland and the world of online casinos in Canada, all in one place.

Thank you for your continued support, and happy gaming!

Portland is a city of bridges, and boy, do those bridges have a lot of history. We…

Here’s an absolute treat of a story for you. We’re diving into one of our…

Whether you’re new to town, or you’ve been pandemic-bound, Portland is still thriving. It continues…

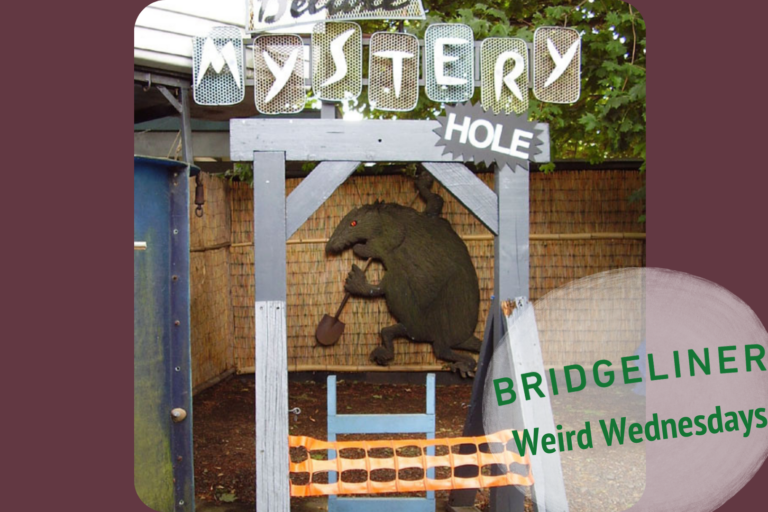

It’s Wednesday. And you know what that means … It’s time to get weird. Every…

It might seem like Tinder, Bumble, and Hinge are the only ways to find a…

“I have dated in San Francisco, Seattle and Colorado, and… though there were bad dates,…